Book review: The Two Jerusalems: My conversion from the Messianic Movement to the Catholic church

(I normally do not review books. However, the following review was completed for The Fellowship of Catholic Scholars. It is an autobiography of faith rather than an academic book, and as such gives a dizzying account of the errors and rabbit holes found in Messianic Judaism, Christian cults, and Protestantism. As such, it might be of interest to some of you 😊)

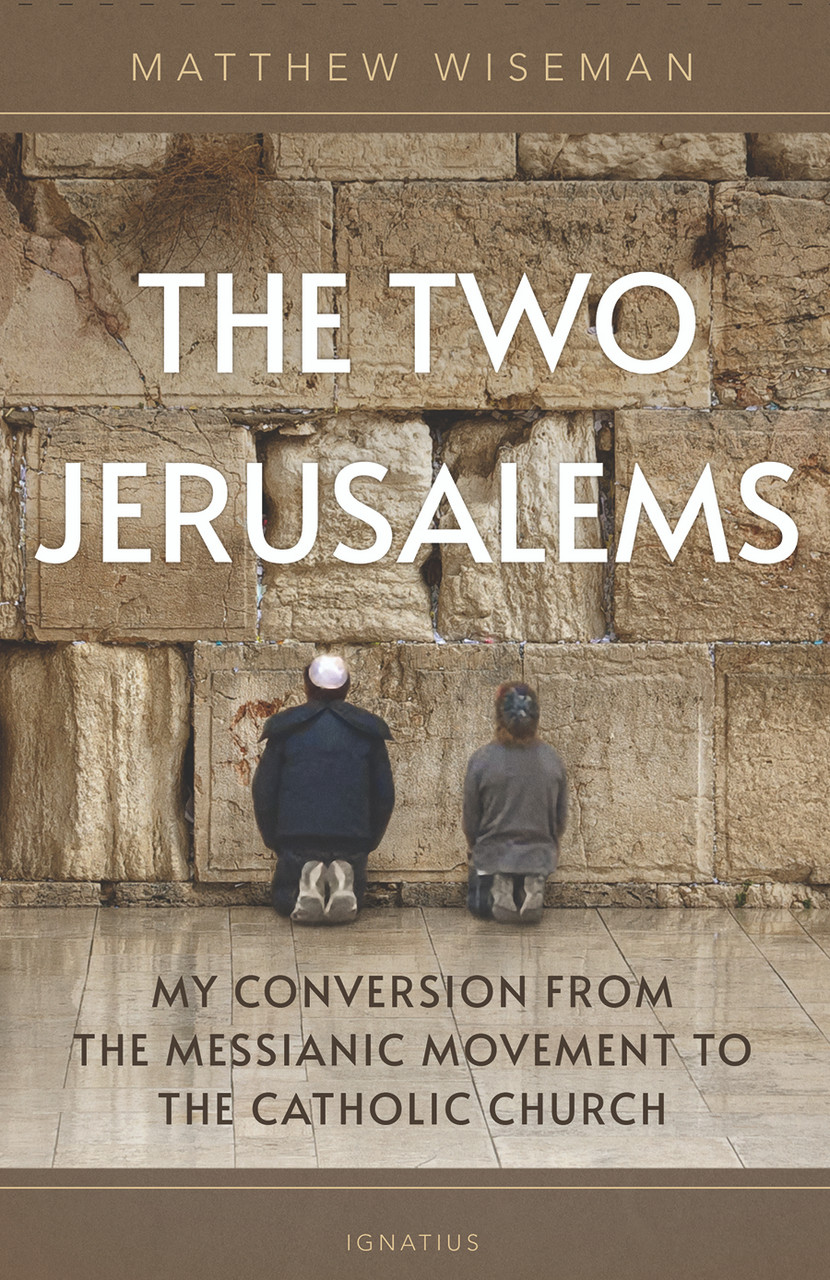

Matthew Wiseman. The Two Jerusalems: My conversion from the Messianic Movement to the Catholic church. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2024. 212 pp. https://ignatius.com/two-jerusalems-tjp/

The 21st century has seen a growing interest in the Judaic roots of Christianity amongst all Christian traditions, so this is a timely book. Wiseman has provided a spiritual genogram in a storytelling style. Sprinkled throughout are the seeds of Catholicism that were planted along his journey. He explains his faith journey with implied parallelism between the nature of some sects in Judaism and Christianity to Catholicism and mainstream Protestantism. In doing so, the reader with a keen eye is receiving a history and theological education within these pages expressed in terms of its social formative effects upon himself and family members.

The author begins by tracing the mostly Protestant roots of his parents: Europeans who settled into the Southern U.S.A. and eventually moved to Texas. His paternal grandfather had been raised devout Catholic but left the church to marry his Methodist grandmother. Both his mother and father were raised Baptist, subsequently dedicating their own children to their Baptist church. They were a deeply religious family, both being active in their church and also making scripture the center of their family life. Like many Protestant traditions, the Baptists believed in personal interpretation; that is, the belief that scripture should be interpreted by the individual under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. This faith/family foundation of libertarian individualism, of a self-defined orthodoxy, becomes a recognizable thread in their search that led them out of Christianity altogether and into the quasi-cult Hebrew Roots Movement.

The change began when the author’s parents desired to attend church services together as a family rather than sending the kids off to their separate Sunday school classes. By age 11, unable to find a church that shared their idea of family worship, the author’s family began practicing their faith in their own home church on Sundays. The children’s homeschool education continued with his mother’s emphasis on critical thinking and investigation. They were not sheltered from classic literature nor raised in a bubble. Rather, their quest for knowledge included even Catholic and Catholic-friendly classics like Tolkien and Lewis as well as Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History and the writings of Josephus. Although in some ways their life became more removed from mainstream Christianity, through books their minds were expanded.

As other families also stepped out of communal worship and into home churches, and as these families began to assemble and bond, perhaps it was inevitable that their personal interpretation of God’s Word would lead them to cult-like movements within Christianity. These movements exist precisely within the fringe of religious society. Libertarian individualism is fundamental in such movements, and the Hebrew Roots Movement was no exception. Wiseman gives clear explanation of their beliefs and his lived experience of it: only accepting the law of Moses and not the oral Torah, practicing the Jewish feasts of the fall season, observing Kosher laws, and more. The ‘guru’ they followed eventually joined with a modern Karaite movement whose founder also believed readers of the Torah were capable of interpreting it themselves. At this point, the author was a young teen. The family’s faith practices expanded to include wearing tzitzit, praying the Shema, and more:

“We waited outside to see the new moon marking the beginning of a month or holy day; we ate ritual meals with our friends late into the night…even getting dressed in the morning took on theological significance” (41-2).

The family participated in “Torah study” groups, sometimes in the facilities of traditional churches. This reclusive immersion into a Torah-alone worldview led the author to rejecting his previously-beloved Christian fantasy literature like Narnia. However, throughout high school years his reading crossed many genres as did his own personal writing. He even was enrolled in an online Catholic course through which he developed Catholic friendships and traveled down a path of forming right reason through his own intellectual engagement and supplemented by classics from authors like Peter Kreeft. This defense of the Christian doctrines “especially the divinity of Christ and historicity of the resurrection…saved me from some of the more dangerous aspects of the Hebrew Roots Movement.” (62) This also led him into textual criticism of biblical passages and opened his eyes to seeing instances of “egregious distortions of evidence.” (66)

Thus, the first decade of Wiseman’s life was a stable, traditional American Christian lifestyle. However, the withdrawal from a church community into their own home church, then frequently branching out into other groups, brought a regular cycle of change in support systems for their family. Yet through it arose his longing for a spiritual home, a study of the esoteric Jewish cults, and a “growing love and longing for ritual” such that he began “to form my life around it” (73). Catholics will recognize the similarities to our beliefs and practices. For example, our adherence to Deuteronomy 6:8 is by the keeping of God’s laws in our minds and deeds at all times—we close the Gospel reading in mass by signing our foreheads, lips and heart as attestation of this. In our homes we bless our food; in both home and church we light candles. Many laypeople, most religious and all priests pray the Psalms in the Liturgy of the Hours. All of these are practices brought over from our Jewish origins.

Additionally, Wiseman learned of the proper manner to interpret Hebrew scripture with four senses: peshat—literal; remez—allegorical; drash—“hidden reference independent of context” (83); and sod—mystical nature of God and one’s encounter with Him. (In Catholicism, the proper manner to study scripture also begins with the literal, and then within that context the spiritual sense. The spiritual sense of scripture is threefold: allegorical, moral, and anagogical senses.) As he fed upon the interpretation of scripture under the authority of tradition, he saw how the disintegration of his family’s faith community occurred precisely because they rejected tradition. All of this unknowingly was forming him for the Catholic faith.

Wiseman’s search led him to discovering Jesus scholarship of the later 20th century such as Geza Vermes’ Quest for the Historical Jesus and E. P. Sanders’ Paul and Palestinian Judaism, as well as concepts such as the community of believers being the mystical body of the Messiah, and of restoration Judaism. With it grew a desire to reject the modern world even in dress, a growing distrust of Christian theology, and eventually rejecting the Trinity as doctrine. By age 18, having spent three months with a Messianic community in Israel, his longing for personal change deepened while at the same time his awareness of not belonging to the Jews increased. “I felt very much like I had my nose pressed up against a windowpane but could not get inside” (116).

Entering into his college years, Wiseman further studied various aspects of Judaism including the Kabbala and prayers of Hasidim, various versions of Siddur, and views of tradition as either a primary or secondary authority used for Torah interpretation. His studies at Baylor University catapulted him into deeper and frenzied discovery of the nuances in both practices and perspectives of Judaism, especially the place for tradition. It was here that he came to understand “that the tradition had made the Bible—that they were bound up in each other and inseparable” (132). Seeking to develop his own theory of hermeneutics, he found the transfer of authority for tradition took place through ordination, the laying on of hands, from one rabbi to the next. It was reading of the sanity of Christianity in G. K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy that shifted Wiseman’s paradigm. Chesterton’s example of a man being the right height and shape, yet a tall man thinks him to be short and a short man thinks him to be tall, immediately opened his eyes to seeing he himself as one of the ‘mad’ critics of Christianity’s sanity.

Over time, Wiseman’s eyes opened to the necessity of Apostolic succession and Church tradition to know what scriptures belong in the bible and its proper interpretation. His questions inform us as to the differences of opinions not just with varied Hebrew and Christian sects but also Protestants and the Church of the East. “Even though I did not yet understand the justification for traditional Christianity’s relationship to the Torah, my conversion was based not on my personal ability to answer such questions but on my personal inability to do so.” (160) He ceased his Jewish rituals and sacramentals, leaving him detached from the Jewish identity which he had adopted and “which they established” (161).

Having found what he thought was the church which by external appearances seemed most ancient and traditional—the Orthodox Church—he discovered the liturgy quite distant from the Jewish practices of the early Christians. With reservations, he migrated into the Anglican church which was a traditional low mass form and in which association to ancient customs was visible. His description of this part of his journey takes the reader through liturgical explanations of both that which resonated with Judaism and that which was lacking. This brought him away from the many sects that had splintered from both Judaism and Christianity and steered him back into Christendom. The Anglican Book of Common Prayers reformed him into a Trinitarian faith. Worrisome elements of Anglicism remained, however, particularly The 39 Articles which in his mind was Lutheran. His interest in the Anglican Church was “it seemed to be the heir of English Catholicism, and I wanted to keep far away from Protestantism with its lack of belief in authority of the tradition” (167). Having been told the articles are open to interpretation, he chose his own interpretation and entered into communion with the Anglican church. He found it refreshing to read scripture “honestly and without an agenda” (171), not trying to make it fit into preconceived ideas. He began to understand the Torah as teacher of the law of love (171). But his fuller understanding of Christianity came from the writings of Cardinal Josef Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) and Cardinal John Henry Newman. Meanwhile, he witnessed the divisiveness in the Anglican church which led to the extended subdenominations of Anglicanism, and the variety of opinions on doctrinal truth such as the Real Presence. Allowing Ratzinger and Newman to form him led him closer to the Roman Catholic Church. And its recognized authority was necessary to the unity prescribed in Ephesians 3.

As Wiseman explains his journey, the reader is walked through a scattering of errors and weaknesses he found in Anglicanism while seeing the correct answers in the Catholic Church. Yet all that was good and true in the Orthodox and Anglican Churches remained with him, ranging from praying the rosary to a lived understanding of Mary’s representation of the unity of the Church. This unity, and subsequently the necessity of Tradition, eventually brought him into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church. Acquiring a book of “The Hours” (as St. Benedict described them), he “found the liturgy I had been looking for ever since high school” (204). He had even tried to create his own liturgy in those early years of exploration, not knowing this and other treasures already existed in our ancient Catholic heritage. The reader can imagine his joy of having this lifelong hunger satisfied.

The book is brief (212 pages) but rich in detail with numerous references for further exploration by the reader. Usefulness of the book extends beyond personal enrichment to also providing good discussion in book studies for teens and adults. As Dr. John Bergsma stated in his recommendation, it is “like a course in fundamental theology in narrative form” as Wiseman takes us through a “dizzying” array of religious movements. Explaining the beliefs and practices of these movements and religions provides the reader with an understanding of both the religion itself as well as how Protestant individualism disposed Wiseman and his family to following one idealogue after another. Throughout the book, the author explains his rationale and critiques as he leads the reader along his path of discovering the Jewish roots of Jesus and Catholicism. In this 21st century, many American Christians of all traditions have searched to discover ancient Christianity, often resulting in a blending of their faith with (or leaving it altogether for) Messianic Judaism. Wiseman’s journey demonstrates how that which they truly seek is found in our Holy Catholic Church.

Thank you for caring and sharing appropriately...

Consecrated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Except where noted, all design, writing and images ©2024 by Debra Black and TheFaceofGraceProject.com. All Rights Reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including downloading, photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission or to report violations please email: thefaceofgraceproject@gmail.com